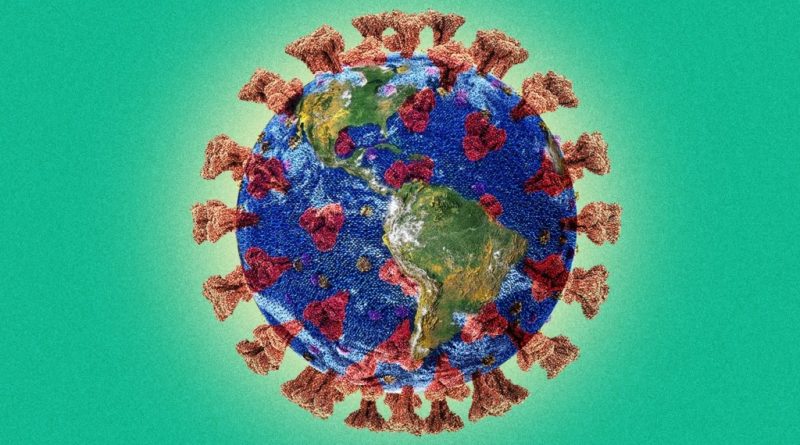

The coronavirus outbreak is part of the climate change crisis

Climate Action should be central to our response to the COVID-19 pandemic

The speed and scope of the coronavirus outbreak have taken world governments by surprise and left the stock market reeling. Since the virus first appeared in China’s Hubei province, it has infected over 700,000 people and killed more than 33,000 across the world in less than six months.

The interconnectedness of our globalised world facilitated the spread of COVID-19. The disruption this continues to cause has made evident societal dependence on global production systems.

The pandemic has forced governments into a difficult balancing act between ensuring public safety and wellbeing and maintaining profit margins and growth targets. Ultimately, the prospect of a large death toll and the collapse of health systems have forced countries to put millions of people on lockdown.

These sweeping and unprecedented measures taken by the government and international institutions could not but make some of us wonder about another global emergency that needs urgent action – climate change.

The two emergencies are in fact quite similar. Both have their roots in the world’s current economic model – that of the pursuit of infinite growth at the expense of the environment on which our survival depends – and both are deadly and disruptive.

Also Read: Coronavirus: ‘Nature is sending us a message’, says UN environment chief

In fact, one may argue that the pandemic is part of climate change and therefore, our response to it should not be limited to containing the spread of the virus. What we thought was “normal” before the pandemic was already a crisis and so returning to it cannot be an option.

The common roots of COVID-19 and climate change

Despite the persistent climate denialism in some policy circles, by now it is clear to the majority across the world that climate change is happening as a result of human activity – namely industrial production.

In order to continue producing – and being able to declare that their economy is growing – humans are harvesting the natural resources of the planet – water, fossil fuels, timber, land, ore, etc – and plugging them into an industrial cycle which puts out various consumables (cars, clothes, furniture, phones, processed food etc) and a lot of waste.

This process depletes the natural ability of the environment to balance itself and disrupts ecological cycles (for example deforestation leads to lower CO2 absorption by forests), while at the same time, it adds a large amount of waste (for example CO2 from burned fossil fuels). This, in turn, is leading to changes in the climate of our planet.

This same process is also responsible for COVID-19 and other outbreaks. The need for more natural resources has forced humans to encroach on various natural habitats and expose themselves to yet unknown pathogens.

Also Read: Asia’s rapid urbanisation, deforestation linked to deadly viruses

At the same time, the growth of mass production of food has created large-scale farms, where massive numbers of livestock and poultry packed into megabarns. As socialist biologist Rob Wallace argues in his book Big Farms Make Big Flu, this has created the perfect environment for the mutation and emergence of new diseases such as hepatitis E, Nipah virus, Q fever, and others.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that three out of four new infectious diseases come from human-animal contact. The outbreaks of Ebola and other coronaviruses such as MERS, for instance, were triggered by a jump from animal to human in disturbed natural habitats.

In the case of COVID-19, it is suspected that the virus was transmitted to humans at a “wet market” in the city of Wuhan, where wildlife was being sold.

The mass-scale breeding of wild animals, including pangolins, civet cats, foxes, wild geese, and boar among many others is a $74bn industry in China and has been viewed as a get-rich-quick scheme by its rural population.

The origin of the virus makes it a perfect example of how the way capitalism commodifies life to turn it into profit can directly endanger human life. In this sense, the ongoing pandemic is the product of unrestrained capitalist production and consumption patterns and is very much part of the deleterious environmental changes it is causing.

The failure to contain it is also due to the capitalist drive of the global economy. In the United States, some have claimed that profit losses from the freezing of economic activity are not worth closing the country for business for more than 15 days.

The World Bank Group has also recently stated that structural adjustment reforms will need to be implemented to recover from COVID-19, including requirements for loans being tied to doing away with “excessive regulations, subsidies, licensing regimes, trade protection…to foster markets, choice, and faster growth prospects.”

Also Read: Relation between coronavirus and global warming: Climate crisis changes disease pandemics

Doubling down on neoliberal policies which encourage the unrestrained abuse of resources would be a catastrophic prospect in a post-COVID-19 world. The suspension of environmental laws and regulations in the US is already a frightening sign of what returning to “normal” means for the establishment.

Climate change is happening

Although both COVID-19 and climate change are rooted in the same abusive economic behaviour and both have proven to be deadly for humans, governments have seen them as separate and unconnected phenomena and have therefore responded rather differently to them.

The vast majority of countries around the world – albeit with varying degrees of delay – have taken strict measures to curb the movement and gathering of people in order to contain the virus, even at the expense of economic growth.

The same has not happened with climate change. Current climate change measures have taken little heed of the scale and progression of the environmental changes we are experiencing. Climate change does not follow four-year election cycles or five-year economic plans. It does not wait for 2030 or 2050 Sustainable Development targets.

Various aspects of climate change progress at different speeds and in different locations and although for some of us these changes might not be obvious or palpable, they are happening. There are also certain thresholds which if crossed will cause change to be irreversible – whether in greenhouse gas concentration in the atmosphere, the loss of insect populations or the melting of the permafrost.

And while we do not get daily updates on the death toll caused by climate change, as we do with COVID-19, it is much deadlier than the virus.

Global warming of 3C and 4C above pre-industrial levels could easily lead to a series of catastrophic outcomes. It could severely affect our ability to produce food by decreasing the fertility of soils, intensifying droughts, causing coastal inundations, increasing the loss of pollinators, etc. It could also cause severe heatwaves across the world, which have already proven increasingly deadly both in terms of high temperatures and the wildfires they cause, as well as more extreme weather phenomena like hurricanes.

Pursuing the UN Sustainable Development Goals, carbon offsetting schemes, incremental eco-efficiencies, vegan diets for the wealthy and other similar tactics will not stop climate change because they do not discourage mass industrial production and consumption but simply shift their emphasis. Such approaches will never work because they do not entail the necessary radical change of our high-powered lives that is required to force us to slow down and reduce our emissions.

The rapid response to COVID-19 around the world illustrates the remarkable capacity of society to put the emergency brake on “business-as-usual” simply by acting in the moment. It shows that we can take radical action if we want to.

Lockdowns across the world have already resulted in a significant drop in greenhouse gas emissions and pollutants. In China, for instance, the lockdown caused carbon dioxide to drop by at least 25 percent and nitrogen dioxide by 37 percent.

Taking action

Yet, this temporary decrease in greenhouse gases should not be a cause for celebration. The fact is that as a result of the lockdowns, millions of people have already lost their jobs and billions will probably struggle amid the economic downturn the outbreak is causing.

While some have called for climate change to be just as drastic as the one undertaken in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, it should not be. We need a just climate transition which ensures the protection of the poor and most vulnerable and which is integrated into our pandemic response. This would not only reverse the climate disaster we are already living in but also minimise the risk of new pandemics like the current one breaking out.

The just climate transition should involve economic reforms to introduce “planned degrowth” that puts the wellbeing of people over profit margins. The first step towards that is ensuring the stimulus packages that governments are announcing across the world are not wasted on bailing out corporations.

We must avoid at all costs a situation where unscrupulous big businesses and state actors are allowed free reign to reinforce appalling global inequality while the rest of civil society is quarantined at home.

We should demand that government funds are instead allocated to decentralised renewable energy production in order to start implementing the Green New Deal and create new meaningful jobs amid the post-COVID-19 economic crisis. In parallel, we should ensure the provision of universal healthcare and free education, the extension of social protection for all vulnerable populations and the prioritisation of affordable housing.

The current response to COVID-19 could help usher in some of these changes. It could get us accustomed to lifestyles and work patterns that minimise consumption. It could encourage us to commute and travel less, reduce household waste, have shorter work weeks, and rely more on local supply chains – i.e. actions that do not hurt the livelihoods of the working classes but shift economic activity from a globalised to a more localised pattern.

Obviously, the conditions surrounding COVID-19 are not ideal, but the rapid and urgent actions in response to the virus and the inspiring examples of mutual aid also illustrate that society is more than capable of acting collectively in the face of grave danger to the whole of humanity.

Author: Vijay Kolinjivadi, a post-doctoral fellow at the Institute of Development Policy at the University of Antwerp.

This was originally published by aljazeera.com