How do roads impact wildlife, and why should anyone bother?

The Centre has asked Karnataka to consent to allowing night traffic on the highway passing through Bandipur Tiger Reserve. It’s a question with no easy answers.

Wild animals are vulnerable to vehicular traffic passing through forests, especially at night when, blinded by bright headlights, even swift species like cats freeze. Over time, as animals learn to avoid roads, busy multilane highways become barriers that hinder wildlife movement, fragment populations, and restrict gene flow. By blocking access to potential habitats, roads, railway lines and irrigation canals act as a major contributor to habitat loss.

India’s policy

In September 2013, the National Board for Wildlife (NBWL), the apex advisory body to the central government on all wildlife-related matters, said no to new roads through protected forests, but was open to the widening of existing roads with adequate mitigation measures irrespective of the cost, only if alternative alignments were not available. The government accepted this as policy in December 2014. In February 2018, the NBWL made it mandatory for every road/rail project proposal to include a wildlife passage plan as per guidelines framed by Wildlife Institute of India, an autonomous wildlife research body under the Environment Ministry. However, features like underpasses are unlikely to suffice in dense wildlife-rich forests where too many animals compete for space.

Elsewhere too

Roads have destroyed tropical rainforests in South America, Asia and Africa. Though under severe pressure, the Amazon rainforests still hold over 1 million sq km of no-go zones, including national parks and territories for indigenous peoples in voluntary isolation. In North America and Europe, where the road network is extensive and wildlife density lower, wildlife passageways are more common. These features are seen in Malaysia and Kenya as well. In many protected areas such as South Africa’s Kruger National Park and Botswana’s Moremi Game Reserve, night traffic is prohibited.

Bandipur story

In July 2008, Karnataka closed night traffic on the Mysore-Mananthavadi highway passing through Nagarhole Tiger Reserve. This, and reports of frequent roadkills in Bandipur, prompted the Chamarajnagar district administration in June 2009 to restrict vehicular traffic between 9 pm and 6 am on two national highways passing through the reserve. Protests by Kerala, however, led to the order being withdrawn.

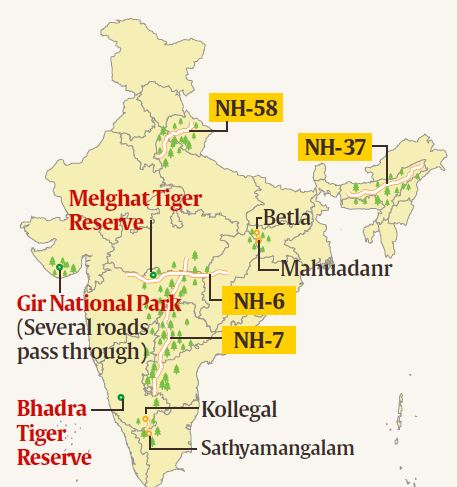

After a PIL was filed, Karnataka High Court restored the ban on night traffic in July 2009. After the final order came in March 2010, Karnataka spent Rs 75 crore to repair an alternative road, but also opened the forest highway to 12 state transport buses and emergency services during restricted hours. The state’s night traffic ban was subsequently replicated in Tamil Nadu (Mudumalai Tiger Reserve) and Gujarat (Gir National Park).

After the Bandipur matter went to the Supreme Court, the court in an interim order asked Karnataka and Kerala to consider allowing convoys of goods vehicles at night — an idea which was eventually discarded. Again in 2015, the Chief Ministers agreed with an expert panel’s recommendation to maintain status quo.

This January, the Supreme Court gave a committee under the Road Transport Secretary, with a representative each from Kerala, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, and the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) three months to file a report. In March 2018, the NTCA recommended maintaining status quo; the following month, Karnataka wrote to the Road Transport Ministry that it wanted to “continue with the existing restrictions”, and that Tamil Nadu agreed.

The new plan

Two days before the July 23 date of submission of its report, the Ministry Secretary asked Karnataka to consent to a proposal to open the road 24×7 with certain mitigation measures. The proposal included elevating the road over four 1-km stretches to provide wildlife passageways below, and fencing the entire highway passing through the reserve with 8-foot-high steel wire barriers. While this may work for elephants if the passageways cover their traditional routes, for territorial animals, just four openings in a 24-km stretch may not suffice. To move between two halves of its territory (split by the highway) a big cat may, for example, have to use a passageway in its neighbour’s territory. If it risks it, a mortal combat is likely; if it doesn’t, it loses access to a part of its hunting ground and, possibly, partners.

The argument for opening up and widening the restricted road is that the alternative road is 30 km longer, and apparently passes through hilly terrain — increasing travel time, fuel consumption, and pollution. Also, it is argued, traffic through a tiger reserve endangers wildlife even during the day, so fencing and passageways are a better idea.

What next

The question is whether a 30-km detour to safeguard one of India’s most wildlife-rich forests is an unaffordable economic burden or a minor concession necessary in the national interest. Depending on Karnataka’s response to the request from the Union Ministry, the committee will finalise and submit its report before the Supreme Court by September 10.

This was originally published by The Indian Express