Environment is the Modi government’s most under-reported disaster

Dhruv Rathee, The Print

Climate change, pollution and biodiversity destruction are some of the most urgent challenges, and a new-generation of revolutionary activists are fighting them.

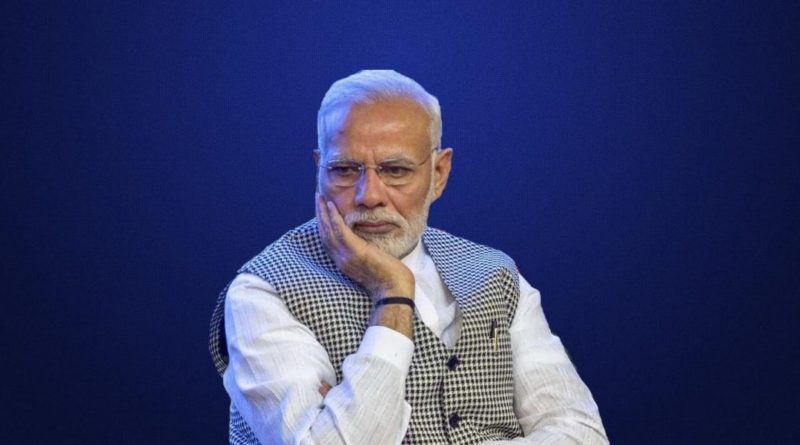

But most political leaders in the world remain lethargic in taking action. And then there are some leaders like Prime Minister Narendra Modi who have started an all-out war against environment in the last five years.

This is also the most under-reported failure of the Modi government. The opposition parties have raised issues like unemployment and farmer crisis, but not environment. The previous UPA government didn’t have much of a stellar record on environment anyway, but what has happened in past five years is unprecedented, which I have mentioned in my Facebook post as well.

The biggest statistical evidence for this lies in the Environmental Performance Index, where India was ranked the fourth-worst country (177) in the world out of 180 countries last year. Five years ago, India was ranked 155th.

The assault began as soon as the Modi government took over in 2014 with the promise of speeding business decisions and removing hurdles to investment. In June 2014, the environment ministry used a bureaucratic shortcoming to remove the ban on setting up of factories in eight ‘critically-polluted’ industrial belts, which was reported in Business Standard.

Environment clearances were eased to allow mid-sized polluting industries to operate within 5-km of eco-sensitive areas, as against the earlier limit of 10 km. Norms for coal tar processing, sand mining, paper pulp industries were also eased.

In August 2014, the number of independent members in National Board for Wildlife (NBWL) was reduced from 15 to just three. More government members in this board meant more government influence – a decision that many say was key to the environmental damage that was to follow. The new NBWL was a mere puppet of the government. Five years later we saw the result – NBWL approved 99.82 per cent of all industrial projects, giving them environmental clearance. A total of 682 projects were allowed from the 687 projects it had to examine. In contrast, under UPA-2, only 80 per cent of the projects got clearance – 260 were allowed out of 328 projects.

The next assault came on 11 December 2017 when Central Pollution Control Board wrote to over 400 thermal power units in the country, allowing them to release pollutants in violation of the 2015 limits set by the government, which were to be followed till another five years. It also wanted newer thermal power plants to follow the new norms of clean technologies set by the government. But as Scroll reported, “even the 16 new power stations that became operational in 2017 had failed to install clean technologies”.

It comes as no surprise that by 2018, 15 of the world’s 20 most polluted cities were in India.

In July 2017, the government tried to undermine the independence of India’s environmental watchdog – the National Green Tribunal. In the past, NGT has often raised pointed questions about anti-environment projects. It is able to do so only because of the autonomy it enjoys. It can only be headed by a former Supreme Court judge or the Chief Justice of a High Court. But the Modi government, through the provision of a money bill, tweaked the rules, allowing a five-member committee, wherein four members could be from the government, to choose the chairperson of NGT. Under the new rules, anyone with ‘at least 25 years of experience in law’ could head the NGT.

Fortunately, this disastrous move was stayed by the Supreme Court.

Laws were changed systematically across the states and at the Centre. Modi government declassified salt pans as wetlands. This move threatens to open up vast lands of salt pans near Mumbai for housing projects.

In BJP-ruled Goa, the state government classified the coconut tree as a grass so that it can be cut without taking permission – a move, many suspected, would benefit the real estate sector. Fortunately, the decision was overturned in 2017.

In 2018, the environment ministry proposed major changes to the National Forest Policy, announced a draft Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) notification and came up with new rules for plastic waste management. All three moves, seen as benefitting the industry, were criticised by environmental activists.

The fight in Gurgaon to save the Aravali and the fight in Mumbai to save Aarey have been documented by the media. These are the last frontiers in this war because these bio-diversity sites are the last remaining green areas in the two cities.

Acts of environmental destruction are being committed across India. A wildlife sanctuary is about to be erased from the face of the earth. In September 2018, Uttar Pradesh government submitted a proposal to the Modi government asking for the ‘Kachhua’ (turtle) wildlife sanctuary in Varanasi to be ‘denotified’. If this proposal is cleared, this wildlife sanctuary will be the first to be erased since the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972 was introduced.

In Madhya Pradesh, the proposed Ken-Betwa river linking project threatens to destroy 4000+ hectare of Panna tiger reserve, a home to critically endangered Gharial species.

In Maharashtra, 53,000 precious mangrove trees will be cut for the famous bullet train project. In Uttarakhand, another environmental disaster took place as 25,000 trees were cut in an ecologically sensitive area for building highways to Hindu pilgrimage sites. This drastically increased the threat of landslides in an already vulnerable region.

In Chhattisgarh, one of the most pristine and dense forests of India is about to be eliminated as the government has given permission for coal mining.

I can go on and on. One ecologically sensitive area after another has been destroyed while laws have been twisted and turned, again and again.

The new BJP manifesto for 2019 elections provides no respite from this ongoing assault. Under the forest and environment section, it boasts of ‘speed and effectiveness in issuing forest and environmental clearances’. This is a catchy euphemism for prioritising construction and industry over ecology and biodiversity. After all, this goes with the ‘ease of doing business’ achievements and voters can be convinced that this is a good thing. There isn’t much on biodiversity protection; there is no commitment towards making India’s environmental institutions more independent and laws more effective.

Our voice is key in the environment debate. More of us need to be champions of the planet.

The author is an activist and YouTuber.